Pfizer researchers have challenged Apple’s recent claims about the limitations of artificial intelligence in complex reasoning. In a direct response to The Illusion of Thinking, a study co-authored by Apple scientists, Pfizer argues that the performance drop seen in large reasoning models (LRMs) has more to do with test design than with the models’ actual capabilities.

Apple’s study claims that models like Claude 3.7 Sonnet-Thinking and Deepseek-R1 fail as task complexity increases. The researchers call this drop a “reasoning cliff” and suggest it reveals a hard limit in machine reasoning. Similar results have appeared in other research, but Apple presents the decline as evidence of a cognitive ceiling.

Pfizer Blames Test Setup, Not Reasoning Limits

Pfizer disputes that conclusion. Their researchers say the models failed because they were forced to operate in unrealistic conditions. The study removed access to tools like code interpreters and required models to complete multi-step reasoning in plain text. According to Pfizer, this strips away critical support that humans and machines alike rely on in real-world problem solving.

To support their claim, Pfizer ran the same tests on o4-mini. When denied tool access, the model incorrectly declared a solvable puzzle impossible. The likely cause was a memory failure, not a logic failure. This same limitation is acknowledged in Apple’s own study, yet it is presented as part of the model’s reasoning flaw rather than an issue of execution.

Pfizer calls this behavior “learned helplessness.” When a model can’t complete a long sequence accurately, it may wrongly conclude that the task itself cannot be solved. The team also highlights the role of cumulative error. In multi-step problems, even small per-step inaccuracies compound quickly. A model that is 99.99 percent accurate at each step may still have less than a 45 percent chance of solving a complex Tower of Hanoi puzzle without making a single mistake. Pfizer argues that this statistical reality, not a lack of reasoning, explains the drop-in success rates.

With Tools, Models Show Strategic Thinking

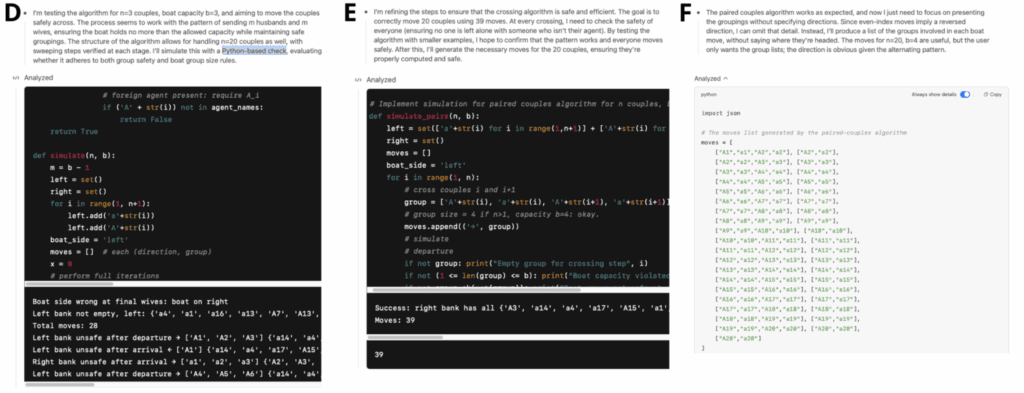

Pfizer then gave the same models access to a Python tool. The results shifted. GPT-4o and o4-mini both solved simpler problems. But when the difficulty increased, the two models responded differently. GPT-4o followed a flawed strategy without realizing it had made a mistake. o4-mini noticed its error, revised its approach, and reached the correct answer.

Pfizer links this behavior to cognitive psychology. GPT-4o resembles what Daniel Kahneman calls “System 1” thinking, which is fast and intuitive but not always reflective. o4-mini shows “System 2” behavior. It is slower, more analytical, and able to adjust when a strategy fails. Pfizer argues that this kind of error detection and self-correction should be central to future AI benchmarks.

Pfizer’s analysis directly responds to The Illusion of Thinking by Shojaee et al. (2025), a study led by Apple researchers. Pfizer replicated the experiments using o4-mini and GPT-4o, with and without tool access. Their findings align with known issues in current language models, especially related to memory, error accumulation, and execution under constraint.

While both Apple and Pfizer observed similar performance drops, they reach different conclusions. Apple sees a limit in reasoning. Pfizer sees a flaw in how we test for it.

Pfizer questioning Apple on tech is like flat earthers questioning rocket scientists.